Update : As of iOS 6, it is now possible to use Network Link Conditioner directly on the device. Additional details can be found in this post.

Note:Â After upgrading to Mountain Lion, Network Link Conditioner was not working for me. Steven has pointed out in the comments below that this can be resolved by removing and re-installing the prefpane. Thanks for the tip, steven!

One shortcoming of testing in iOS Simulator is you don’t get to test how your app does in real world network scenarios. The solution? Network Link Conditioner.

Network Link Conditioner is included with Lion’s Developer Tools. You can install it by going to Applications > Utilities > Network Link Conditioner and double clicking the prefpane file. If you don’t see the Network Link Conditioner folder, you can open Xcode, go to the Xcode menu > Open Developer Tool > More Developer Tools…, then grab the Hardware IO Tools for Xcode download (Apple developer account required). Once you have it installed, open up System Preferences and you should see Network Link Conditioner listed at the bottom under Other.

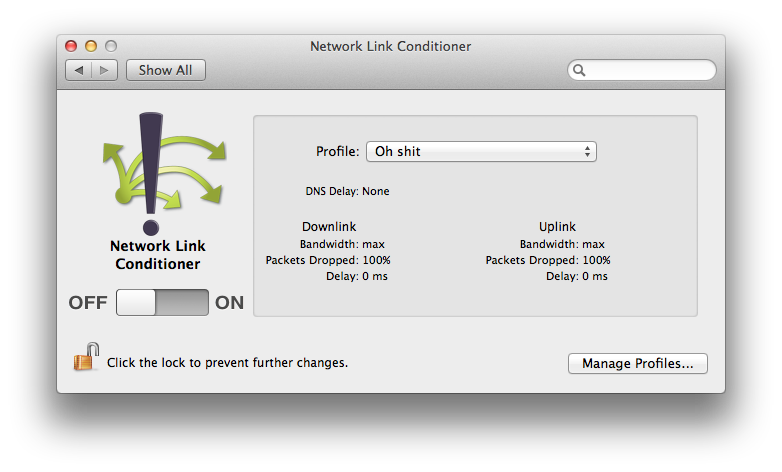

After launching it, you’ll see there is a Profile drop-down that lists a number of preconfigured network scenarios including various 3G and EDGE profiles. If you click on Manage Profiles you can also create your own custom conditions in there to suit any needs you might have (for example, simulating a completely dead network where no traffic gets through). Playing around with my own profiles a bit, I found a pretty good mix with bandwidth set to 85kbps and packets dropped set to 15% for both downlink and uplink. I get a pretty good mix of some things loading and others timing out with those settings.

If you’re using iOS Simulator, you don’t need to do anything special to route your traffic through Network Link Conditioner (except turning it on). However, if you’re testing on a device, you’ll need to proxy your device’s traffic through your computer. The details are beyond the scope of this post, but I will say that I use Charles Proxy for this. I’ll cover the specifics in a later post.

A couple of caveats to note when using Network Link Conditioner. The first is it seems to lock itself about every 5 minutes. So you may find that you frequently need to re-enter your password to turn it on and off while testing. The other drawback worth noting is that Network Link Conditioner is system-wide and has no ability to distinguish between traffic. It doesn’t care about the color of your traffic or the content of its character; it treats all your traffic the same. This means when testing very poor conditions you have to say goodbye to IM, email, loading your ticket tracker, and that sweet dubstep remix you’re playing in the background on YouTube. Obviously this isn’t ideal and I hope that Apple will extend functionality in the future to customize the tool’s reach. It’s for this reason that often times I prefer to use Charles Proxy which has a Throttling feature with similar functionality to Network Link Conditioner, and you can customize which traffic you want it to affect. None-the-less, Network Link Conditioner is a great, easy-to-use, free tool that’s extremely useful in uncovering bugs you may have otherwise missed.

Now that we’ve covered the how, let’s talk a little bit about the why. As shocking as it may be to hear this, cell phones aren’t always connected to a speedy, reliable network. Every thing from a weak signal, to slow public wi-fi, to Sprint’s data network can result in poor network performance for your user and some poor conditions for your app to work under. While you can’t control the quality of the network your users are connected to, you can ensure that your app handles the poor conditions as gracefully as possible. It’s important to use a tool like Network Link Conditioner or Charles Proxy (or a terrible cellular connection) to weed out any bugs that may manifest in these poor conditions and make sure the overall user experience is still a good one.

One big no-no to this will help check for is doing network requests on the main thread. If you’ve ever gotten crash reports with an exception code of 0x8badf00d, you may already be familiar with this problem. Essentially if your app makes network requests on the main thread and it occurs on launch, a slow network could mean your app won’t successfully launch in time and watchdog will kill it before your user even gets it open. This type of issue can be very easy to miss during development and QA because your office wi-fi will likely load things quickly enough to avoid this problem. But as soon as a user in the real world with a poor network tries to use your app, the 1-star reviews will start rolling in.

Once you’ve made sure you don’t see any crashes in your application, turn your attention to the user experience. Even under poor conditions, your application should have some kind of messaging to your users about what’s going on. Failing gracefully is important— in your apps and in life.  A big point of frustration for users can be if your app is loading data (especially if it’s taking a long time) and you’re not conveying that to them in some way. When you’re loading data, tell the user. Using iOS’ network activity indicator icon that’s in the status bar is a good start, but often times it’s beneficial to show a loading indicator within the app, either as an overlay or in the portion of the app where you’ll display the data once it’s loaded.

If your data requests timeout or otherwise fail, once again, make sure you’re telling the user (preferably not with an alert dialog). Tweetbot has an implementation for this that I really like. If your pull-to-refresh fails, you get a nice little notification that slides down from the top to let you know and after a few seconds disappears, not requiring any user interaction and not disruptive to the app’s flow. On a related note, putting a timestamp in your pull-to-refresh bar that says when the last successful update from the server occurred can also be very helpful to users. It’s a simple way for users to see how stale their data is.

Finally, be sure to test bad network conditions on a clean install. Your users may very well be on a bad network the first time they launch your app and not have the luxury of some data already being cached. If your app relies heavily (or entirely) on data requests going across a network, your poor user stuck on a flight with no wi-fi should be able to see something other than completely blank views. Even if your user’s network fails, your app doesn’t have to.